Sassing Back: Rewriting the Politics of Incest

by antoinette nora claypoole

A Book review of Sharon Doubiago’s My Father’s Love

(2009, Wild Ocean Press, San Francisco)

A Book review of Sharon Doubiago’s My Father’s Love

(2009, Wild Ocean Press, San Francisco)

for Infoshop News version

March 2010

“The Lone Ranger is still coming across the purple sage. America in her mask. The mask they wore to nurse you. The you and your sister wore posing for the camera. Behind the mask is a girl with breasts...we sleep in the Petrified Forest...” (pg. 235).

We arrive in Long Beach, Ca. inside another time. Almost feeling the sea winds inside the old Ford. As the handsome man, his “gorgeous wife” move into the American way. We trek through the landscape of a family caught between nuclear, and extended. Between a toxic wasteland and vast compassion. America. Of the 1940’s and 50’s. This is where Sharon Doubiago takes us, Southern California the backdrop, small living rooms and side streets with “hobos” the set. But. It’s not Hollywood. It’s not even surfer girls. Yet. The characters in this true place carry a painful, universal story of exploitation. Incest and rape.

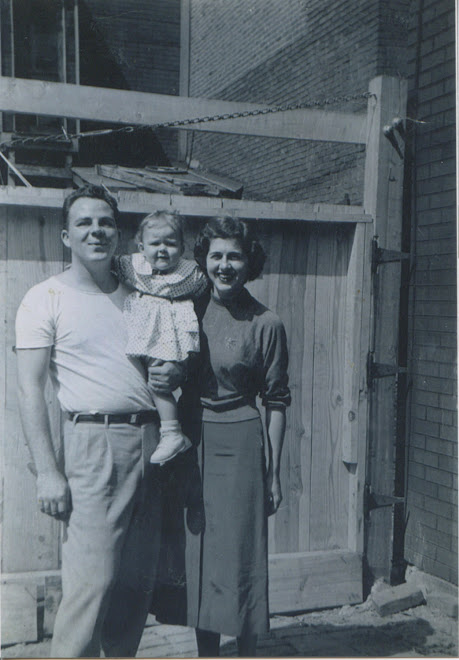

Poignantly, provocatively written by poet Sharon Doubiago—Oregon Literary Arts Award winner/Univ. of Pittsburgh Press prodigy—Father’s Love is neither a reflection of the once trendy, incest victim/malice nor an American sojourn into a glamorized, western, “Golden State”. Of forgiveness. Rather Doubiago’s first volume of this book (Vol. 2 forthcoming) is an intersection of where we’ve been. And where we long to be. An expression of how a young girl, an American woman can and does love and simultaneously defy father/men, sisters/mother, despite the cultural designs of being christened a daddy’s “girl”. Despite being expected to birthday a man who can rape and claim the name of love. Created with tender, poignant vulnerabilities, Doubiago inspires a revival of innocence stolen with literary and actual photos of her family, her self, her longing, included in the book.

Yet. Rather than a rally of hate and loathing often found in varied genres of incest literature, this poetic prose expose—not quite memoir (happily), not ever fiction---reveals, as the subtitle promises, a “Portrait of a Poet as Young Girl”. Doubiago, both muse and historian in this book, depicts with a reverent, oblique love the impact and immaculate deception of the American Dream. Reveals the cowardice of a “loving” father, the betrayal of sister/mother bonds—all with candor and a tender paradox of longing. A longing for connection which ever -informs the detailed, graphic images of a corruption her family--so many of our families--bred/breed.

Despite evidence of incest tucked between “the red bricks outside our front door”. Despite beauty betrayed at a young age via “garage dates” with daddy-- Doubiago brings us My Fathers’ Love while delicately clutching nasturtiums gathered from the cliffs upon which she was born. Yes. She bears roses in her heart. Thorns, yet blooms intact. Petals strewn for us to discover. A pathway to truth in our own lives. She is the finest guide we can imagine to navigate, to survive the feverish climb. Had Sylvia Plath read My Father’s Love she might still be with us, doctored by Doubiago’s poetic candid courage. Seizing, drinking stories which free twisted lies from death due to silencing, Father’s Love is the sculpting of a young woman’s psyche. And a freedom from it’s corruption. By place and people who have the American Dream etched into their daily rivets, Rosie of WW II not far from their vocabulary.

The 1940’s beaches, the mid 20th century places, the Ramona, California of the book resound with memories Doubiago has etched and woven with the threads of western, Americana innocence. Still yearning to return. She tells of place--literal and figurative-- where being “woman”, being girl child is the motherlode of fathers and all others who seize the doctrine of consuming, owning, all that stands in the way of beauty. Repeatedly, just as in the minds of those who have survived it, just as the act of incest lives in flashbacks of “real life” each day, Doubiago tells of a place where innocence is a commodity. In Doubiago’s words, her stories, her chronicles of childhood as a an oldest daughter of a simple “daddy mommy” family living the 1940’s and 50’s of S. California she talks incest in seductive, intriguing yet harsh, tales of ancestry.

Still. Hers is not the anger rant nor the victim chime of loss deconstructed by other “incest” chronicles and writers. Rather Doubiago writes for us a valentine etched into nearly every page of this epic deliverance into a landscape of pain. A song in her genius, poetic storytelling, Doubiago casts a spell over us, the reader, as she weaves this delicate and honest tale of conquest, of sex and being sexed as a young girl. In the name of love Doubiago writes in her most resounding voice to date—surpassing her classic A Book of Seeing with One’s Own Eyes--a tale which is elixir for those of us straining to understand how we have come to love all who have taken our innocence as commodity, have tasted our beauty and “smacked snot” on our hearts.

“I don’t want to run away. I want to stay in my family forever, at least until the confusions are cleared up and they know I’m not jealous and they know how much I love them”(pg 110).

Valentines are more than metaphor in this book.

A confused young adolescent Doubiago painfully describes her first valentine from a crush, in sixth grade. Having already been raped by “daddy”—who was born on Feb. 14th—the images of confusion about love are set.

Doubiago shares with those of us women young enough to still be here and old enough to write the 60’s, courage to prevail. She knows. How many times we have been called liars by those sisters and brothers, mothers and aunties, afraid to speak truth. Naming us “exaggerators” so they can alleviate their fear of facing truth. Doubiago depicts this betrayal phenomena with as much importance as the act of rape itself.

The broken slivers of beer bottled glass betraying bare feet in an urban meadow. She takes us to the window of blindfolds. And helps us take hold of speaking truth despite the aloneness, the negation of those who have witnessed a crime against soul. Doubiago makes a choice to tell us we aren’t alone. We who have, as writers and lovers, been tried and convicted by beloveds everywhere for “having wild imaginations”. During the sentencing being told “no honey. None of that never happened, you weren’t raped”

That is, in My Father’s Love we not only sojourn a taboo with unique tender intensity, but we are driven to lace up our boots and walk the cliffs, the blizzards of self-indulgent lies our sisters and mother’s deny. While they freeze, Doubiago urges them to take shelter. There is no state maintaining these roads during the storms Doubiago documents.

That is, Doubiago is not only a “survivor” of incest but more--she gives us the crack in the wall.

That is, in My Father’s Love we not only sojourn a taboo with unique tender intensity, but we are driven to lace up our boots and walk the cliffs, the blizzards of self-indulgent lies our sisters and mother’s deny. While they freeze, Doubiago urges them to take shelter. There is no state maintaining these roads during the storms Doubiago documents.

“Nights. Everyone’s dead but me and Mama. Then the arrowhead penetrates right in the middle of her forehead splitting her in two. Then the flames, then the whole tribe is storming in on me” (pg. 193).

There isn’t a page one turns in this epic mural of the heart that forgets the witnesses.

In this way My Father’s Love is as much about incest and how we translate it’s persistence as it is about defining love and betrayal in the sassy defiant sway of sisters and mothers. Denying a father’s confession of rape. Right in front of their irreverent senses. Yes. Doubiago in fact stretches far beyond the Anais Nin syndrome of keeping secrets until all the players are “gone”, taming—perhaps for the first time-- “incest literature” to dance in two-step, in wild west literary format, with the sisters and mothers. Forcing them/us to claim a part in the corruption of beauty incest demands.

This place of denial is portrayed as horrific as the act itself.

In Bridget, Doubiago’s sister (Bridget’s “real” name not used in this book), we have not a literary protagonist, rather a metaphor of spite. There are times Doubiago forces us to see in a sister, a loathing that surpasses or at least equals the rape itself--as a person lying in the same room with you while you are taken from your love in the name of love, as that person denies her sister a safe harbor and/or denies witnessing the rape. That is, with Doubiago. Younger sisters are not immune to the desire to slay beauty. There is more we know we as women can do and be and there is less and less Doubiago and her sister “Bridget” will escape.

Doubiago ever vigilant. Asking, still, for their eyes to open and cry with the girl who never cries in her sleep. To weep with. The girl who doesn’t sleep.

In the end, we are transfixed from the perplexing politics, the remiss of old rhetoric which consumes our dreams of a country where at long last a man of color might redeem the toxic currents of power. That is, there is a timelessness in “My Father’s Love” which reminds us that our delusions may be invested in tender men (and women) who appear to be the keepers of our dream and yet are the ones who will most certainly seek their own needs, first. Exploiting our trust in their desire to be trusted.

Make no mistake. In My Father’s Love. The vileness of incest is not dismissed. Nor is it excused, given penance. At the matrix of her work Doubiago seeds the multi dimensional, complex encounters with father. Holy father is challenged. A shroud is lifted. From the subtle rape of a sacred heart The violent rape of her body. The secret rape of her trust. Is depicted without mercy. From “lift your shirt, let’s check your breasts” to “you see you just aren’t as happy as your sister”. Doubiago takes us into the labyrinth of humiliation and shame upon which secret rapists thrive. The altar upon which they pray. And make no mistake. She loves her daddy. Hears his death bed confession of rape. And writes us a legacy which is not exclusive to her family, rather rampant in this American society.

There is no vaccination against such a disease. Doubiago’s father is living testament to this fact. Still. This is not a hate my father confessional book. Not a how-to hymnal. It is a collection of beatitudes to set us free. To know of these things. Doubiago stands in a threshold and invites us into her world. This was her Daddy. She loved him. Knowing full well it could also be our world. As well. She invites us in. To stand strong in our truth. To know we are not alone. That if we feel, we can dispel the lies which others would have us live by. And begin the authentification of self. So desperately craved, so nearly lost.

To stay it straight. My Father’s Love helps us stop lying to ourselves by telling the truth. It makes being a victim of incest unfashionable. Proudly, without apology, Doubiago writes love. She transfixes the vile nature of the event into a sojourn of survival via story. Writing the scenes, threading the tapestry the young girl (or boy) who is raped is now defined by the compassion s/he finds in unsilencing brutality. Thus. Rather than anger and victimization defining life, a connection with others defines survival. We are with her, in her story, and at some odd or brutal intersect, her story, our story merges. And we become One. Surviving together. The condoned brutality of patriarchy. Defying the common bond of lies. Becoming connected in corrupted love.

‘Isn’t it pretty Sharon LuLu?’, he sighs in Tyler, Texas. His hard snaky thing wagging back and forth under the steering wheel. Hives break out across my bare midriff...I worry about his wiry hairs when he has to zip up fast, Mama coming back so happy with roses” (pg 235).

Reading Doubiago one feels. Organically, somatically a subsequent ostracizing of those who rape and commit incest will emerge. At best. They will and can be busted. Not by the law, but by their People. Which once used to be one and the same thing. At least, they will be more easy to recognize, disguised as Father Love, masquerading as family.

In the end Sharon Lura Edens Doubiago gives us a safe home from which we can deconstruct AND reinvent our loss of innocence. A place from which we can release our longing. Doubiago a sorceress. Divining a sense of replenish. In the act of writing as revolution she has given Love a new task. One she herself accomplishes with painful grace: become that which you desire. Not that which has desired you. Insisting we redefine a father’s love Doubiago infuses our crucial task with a tender, painful, genius. A plethora of craft and heart. This book, this project, chronicles our despair -and in the making defines our possibilities. That is, Sharon Doubiago in My Father’s Love becomes a model of freedom, that others may plan our escape.

In the end Sharon Lura Edens Doubiago gives us a safe home from which we can deconstruct AND reinvent our loss of innocence. A place from which we can release our longing. Doubiago a sorceress. Divining a sense of replenish. In the act of writing as revolution she has given Love a new task. One she herself accomplishes with painful grace: become that which you desire. Not that which has desired you. Insisting we redefine a father’s love Doubiago infuses our crucial task with a tender, painful, genius. A plethora of craft and heart. This book, this project, chronicles our despair -and in the making defines our possibilities. That is, Sharon Doubiago in My Father’s Love becomes a model of freedom, that others may plan our escape.